Organisational growth and development

Introduction

From Conflict to Co-operation aims to help co-operatives not only to deal with conflict when it arises (Chapter 1), but also to avoid unnecessary conflict by:

- Improving communication skills – Chapter 2

- Improving meetings and decision-making – Chapter 3

- Managing change caused by organisational growth and development – this chapter

- Clarifying the roles and responsibilities of the board – Chapter 5

Chapter 4 explores the tensions that can arise as a co-operative develops and identifies tools, techniques and approaches which will help as the co-operative experiences growth and change. It looks at managing change, policies and procedures to address issues such as recruitment, induction and appraisals or personal reviews. It also provides a summary of tools to facilitate participative strategic planning.

Issues of organisational growth and development

The need to acquire new skills and develop new attitudes as the co-operative moves through the early start-up phase to a more stable phase of development can cause friction. However the business is organised – whether it has adopted a hierarchical structure with delegated authority or whether it’s run on a collective basis – communication is key.

Different ways of communicating will emerge based on everybody’s tastes and preferences. You may be happy to attend in person meetings, or you may find online meetings more feasible or you may prefer to use social networking sites on your mobile. However you relate, it’s essential that the co-op is aware of everybody’s preferences and habits and facilitates information sharing using appropriate modes of communication.

The success of Elland-based worker co-operative Suma Wholefoods demonstrates the benefits of freeing up the 200-strong workforce to be leaders, rather than controlling them with managers.

Case study: Suma Wholefoods

Suma is Europe’s largest co-op of its kind and the UK’s largest independent supplier of wholefoods. It is a worker co-operative, committed to ethical business and specialises in vegetarian, vegan, fairly traded, organic, free-from, ethical and sustainable products. Established in 1977, Suma members believe that being a worker co-operative is one of the fundamental keys to their success.

Suma operates a truly democratic system of management. An elected Board implements decisions and business plans, overseen by an elected Member Council, and supported by area leaders. Day-to-day work is carried out by self-managing teams of employees, supported by team coordinators. Everyone is paid the same wage, irrespective of the job they do, and everyone enjoys an equal voice and an equal stake in the success of the business.

Another key feature of Suma’s structure and working practice is multi-skilling. Members are encouraged to get involved in more than one area of business, so individuals often perform more than one role within the co-operative. This helps to broaden the skills base and gives every member an invaluable insight into the bigger picture.

This chapter addresses tensions that arise as a result of change – changing roles for example, that can lead to stress for founder members as they lose control over ‘their’ co-operative, as well as for newer members who may feel they lack the insights and experience of early members. We will look at how to help members adjust to change and explore some of the reasons individuals may resist it.

We consider the potential for increasing tensions as the co-operative develops. For example, from a lack of agreed, written and accessible policies and procedures; from inadequate recruitment and induction procedures; and from misunderstandings around the different approaches to carrying out employee or member appraisals. Finally we explore participative approaches to strategic planning and some tools and techniques.

Change

Change is taking place all the time, all around us. In our co-operatives it is taking place not only when we introduce a new policy or develop strategy, it’s also taking place in the canteen or in a chat between colleagues in a corridor. So when we plan for change, we need to be aware that formal channels of communication are inadequate, we need to take account of these informal channels too, and of the continuing conversations that are taking place at all levels.

A moment’s reflection will remind us that planned change never comes about entirely in the form it was intended. This is because of the constant interweaving of the intentions of all the co-op’s members. Gap analysis cannot reflect this reality: we need to take into account insights that will occur as the plan is implemented; the unforeseen impact of our actions; and influences of the surrounding environment.

People don’t resist change out of sheer obstinacy. There are many reasons why an individual might refuse to go along with a decision which is of benefit to the co-op as a whole.

They may have developed expertise in a specific task which they enjoy or have earned a position of respect from the old way of doing things. Or more negatively, they may, in a larger co-op, have carved out a little empire for themselves which is of benefit to them personally but not perhaps to the wider co-op? Those implementing the changes must know they have the support of the whole co-op, because this person will fight tooth and nail to hold on to their privileges.

Change Curve theory helps us consider how people might react to change in order to understand how they are feeling and how to support them as the changes are implemented. It is a model based on the work of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross which proposes that people go through three transitional stages – shock and denial, anger and depression and acceptance and commitment – as they react, reject and finally accept and commit to the changes. This theory has limitations however, as it views change in a linear, sequential way.

Perhaps the processes of organisational change might be more accurately reflected by the Emergent Change model, which recognises that change rarely follows a simple sequence of planned phases:

- Some phases may take several iterations to complete

- Discrete one-off phases may get delayed, whilst others continue

- One-off phases such as governance approval, may become complicated by being only partly completed, or by gaining approval only in principle, or subject to alternative funding sources being identified

- Requirements often change or evolve during the change process

Change is more likely to succeed when this near chaotic reality is recognised, so that plans are adapted to reality rather than attempting to adapt reality to a convenient linear process. To effectively manage change, we need to recognise that the process is cyclical and constantly evolves. And that there will be a number of activities that may be one-off, iterative, or phased with intervening delays

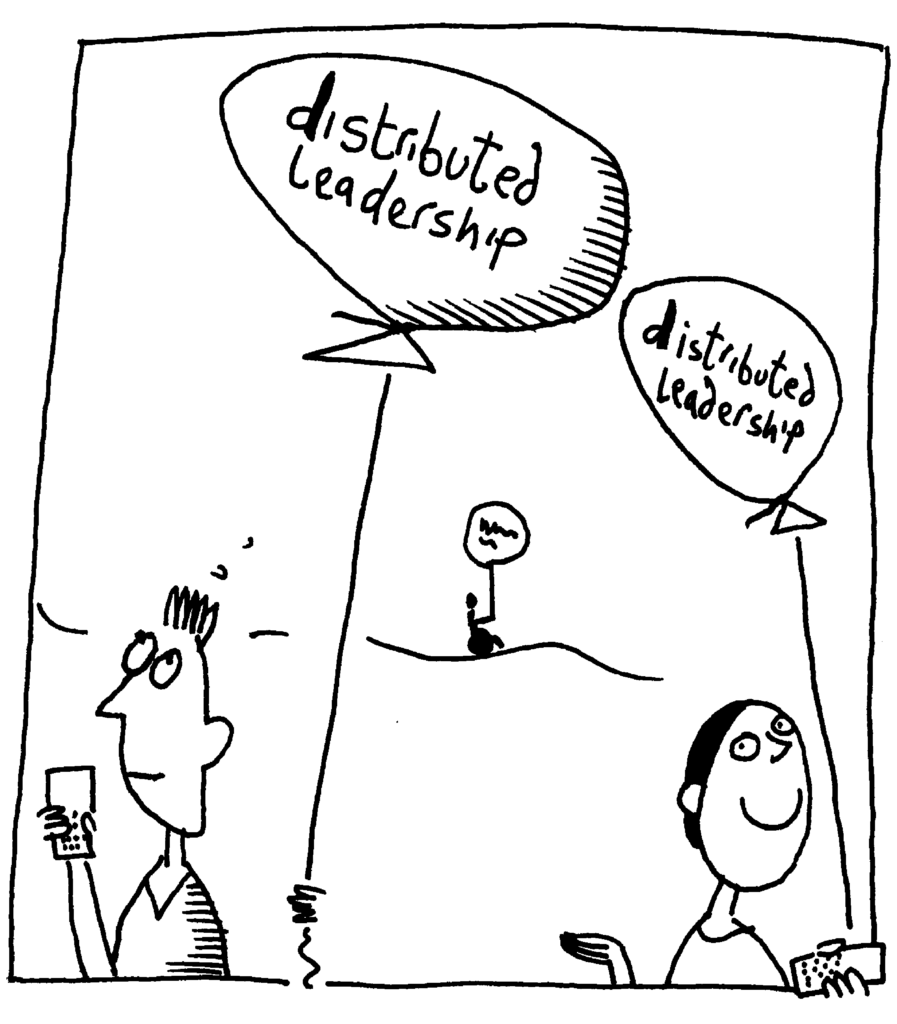

Founders syndrome

Perhaps one of the most common and potentially damaging conflicts arising from change is what’s become known as Founders Syndrome. It happens when founder members’ views and attitudes have become embedded in work practices so that changes needed because of growth are ignored and opportunities lost.

The entrepreneurial dynamism and drive of the founders whose vision got the co-operative off the ground can sometimes be an obstacle when the strategies that worked to grow the organisation during its start-up phase are no longer appropriate.

Co-op founders are often highly committed and motivated people concerned only with the good of the co-operative. Founders syndrome is rather a problem of governance, since newer members may believe that the founders’ skills, experience and knowledge gives them a superior understanding of the situation and therefore lack the confidence to challenge them.

The way forward is for everyone – including the founders – to recognise and acknowledge the problem, and to address it together. You might take stock by holding a risk management exercise, asking some hard questions. What if the founders leave? Who would take take on their roles? Where is the vital information and the contacts for marketing, financial management or contract negotiation to be found? It’s helpful to hold regular strategic planning events, as well as training and/or mentoring programmes to ensure that founder members’ experience, skills and knowledge is shared.

It is also helpful to recognise that new recruits can often see opportunities that are invisible to ‘old hands’ and to let them try. Maybe a fresh approach will work differently this time? Maybe circumstances have changed?

Development

Communication and sharing information

Your co-op may have been started up by a group of friends or neighbours, or might have arisen out of a group with common aims, such as people connected to a campaign or community group. It might be a conversion, where employees have bought out a retiring business owner. However it began, it is likely to consist of people with largely similar views on the aims of the co-op and how it will work. Communications may have been informal, with information shared casually and irregularly. You may be able to make assumptions about each other’s attitudes and values because, in the main, you share them.

As the co-operative develops you will need new skills, knowledge and experience. Once the group grows to more than about seven people, informal and casual communications become counter-productive, because some people will miss out. Assumptions you may have been able to make in the past about attitudes and values may not be reliable, and, as a result, conflict can arise. As the co-op grows, there begins to be a need for a drawn-up organisational structure, with clear lines of responsibility and accountability, and clarity about decision-making. As ever, effective channels of communication are key.

In her paper The Tyranny of Structurelessness, Jo Freeman points out there is no such thing as a group with no structure, and that an apparently leaderless group will have leaders but they will have emerged on the basis of access to resources, charisma, popularity or some other characteristic. Such leaders are not accountable, and since they were never elected, they can never be unelected. It’s better to be clear about where authority lies, and how those that have it can be held accountable and removed from power if necessary.

It may be difficult for founders to acknowledge the need to do things differently – new systems need time to embed themselves in day-to-day activities and need to prove their effectiveness over the old informal way of doing things.

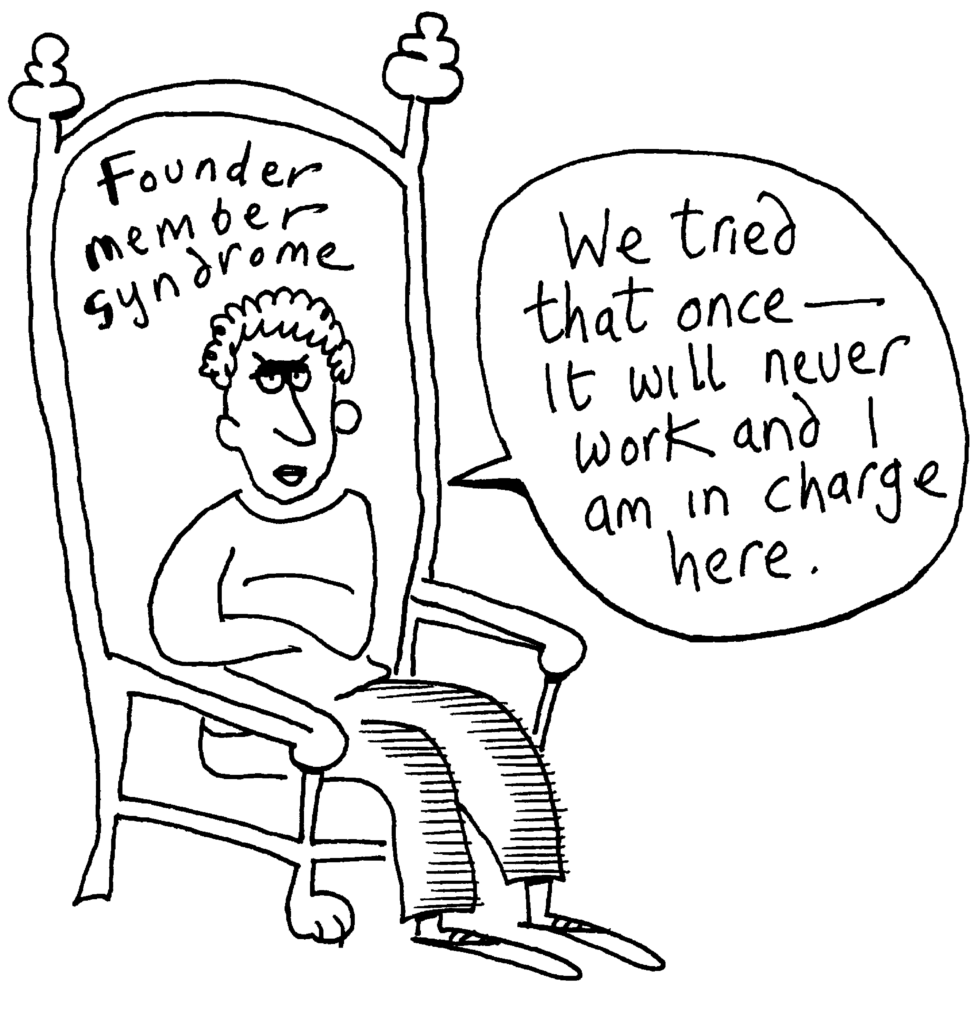

However, unless it is made clear to new members or recruits how things work, how to find out what they need to know to do their job, or how to initiate new projects or contribute new ideas, you will miss out on the energy, creativity and fresh focus of new recruits. There’s a fine line to be walked between valuing past experience and being too ready to dismiss new recruits’ ideas with that most dispiriting line: “Oh we tried that before and it didn’t work…”

Information which, so far, has been in someone’s head, or stored at someone’s house, now needs to be available to all. This might be a business plan, annual accounts, budgets, action plan, mission statement, or your governing document. Whether it’s on paper or an electronic document it needs to be in a clearly labelled file and every member should have access to it.

Meetings which, to date, may have been held in someone’s front room, or upstairs in the pub will now need to be held at a time and a venue accessible and appropriate for all members. It might be useful to draw up ‘standing orders’ for meetings, including:

- When and where they are held

- How to get items on to the agenda

- What the quorum is (how many people need to be in attendance to make decisions)

- Any ground rules, such as turning off or muting mobile phones; no interrupting; respect each other; and punctuality

Leadership

If your co-operative is a conversion from a private enterprise or if you have recruited people who previously worked in private enterprise you might find it useful to consider how much we need to ‘unlearn’ previous assumptions about how business should be run.

TV programmes such as The Apprentice or Dragons’ Den lead us to believe that all businesses are focused on a return on investment for shareholders; they have a hierarchical structure, with workers at the bottom who obey managers; and in turn managers who obey the board, which in turn is looking out for the interests of the shareholders.

We come to believe that this capitalist model is the only way business can be organised, because it is the only model we are presented with. A good way of understanding how a co-operative is different from a private enterprise is to recognise that in the co-operative model ‘Labour hires Capital’, which means that the members (the labour) use capital as a resource for running the business for the benefit of themselves and the community. On the other hand, in the private enterprise model, capital uses labour (the workforce) as just another resource for making profits for owners and investors. (This is why in a co-op we talk about Human Relations rather than Human Resources, to emphasize that point).

Co-operatives need to recruit (or be prepared to train) people with an understanding not just of the market environment of the enterprise but also its social aims and democratic management approach and style. Unless we help members understand that the co-op model is different, there will always be scope for misunderstandings, miscommunication and conflict.

A co-operative is a democratically managed organisation, which means that members make up the sovereign body of the co-operative at the Annual General Meeting (AGM) with every member having one vote. It does not mean that every member has to be involved in every decision – or you’d never get any work done! Depending on your structure and governing document, there may be a board or a management committee, with oversight of operations and responsibility for implementing a business plan, or your co-op may be governed collectively by all the members. Whatever the organisational structure, the sovereign body is always the members at the AGM.

It’s not leadership or even management that is wrong, but leaders as an elite and management as status. We need leadership as a behaviour of many and management as a function to be fulfilled by the many.

New recruits are often at a loss to understand how such an organisation is managed, either leaving the decision-making to more experienced members or seeking to get involved in every decision.

For effective decision-making the structure needs to be based on delegated authority, autonomy and accountability. Individuals (in their job descriptions), and teams, departments, sub-groups, working parties (in their terms of reference) have decision-making authority, perhaps up to a certain budget limit, and they are accountable to all the members either through regular reports to the general meeting or to the AGM. Then they are trusted and left to get on with it. Leadership in a co-operative is distributed, democratic and accountable. Everyone can show leadership in different areas and in different ways.

Co-operative leadership involves:

- Being assertive, understanding body language

- Being emotionally literate

- Having good listening skills

- Being open to other points of view

- Not being defensive

- Seeking consensus

- Modelling co-operative behaviour

- Functioning well in chaos

- Knowing when to use humour

- Knowing when to follow and when to lead

- Having good facilitation skills

- Again, remember that for some people, conveying appropriate body language or facial expressions can be challenging.

You might enjoy The Tao of leadership where John Heider has adapted the laws of effective leadership as set down by ancient Chinese sage Lao Tzu.

Policies and procedures

To ensure that all members have access to the information they need to perform their role, and to avoid spending time in endless meetings, you’ll need written policies and procedures that spell out how the co-operative intends to achieve its objectives, what the various tasks are and how they should be fulfilled.

There is a whole range of areas where written policies and procedures are necessary, including Human Relations (aka Personnel), Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, Anti-racism, Health and Safety, procedures to support sound financial management, or training policies to ensure that members develop skills they need to run the business.

Policies and procedures will vary according to the type of co-operative, economic sector, stage of development, and how many members, employees or volunteers you have.

Policy is the way an organisation works, written down as guidance for members. Procedure generally means the way in which policy is carried out. For example, an Equality, Diversity and Inclusion policy needs accompanying written procedures, so that when staff are interviewing prospective candidates or dealing with a complaint they can be sure they are complying with the policy.

Member job description

In worker co-operatives, it’s helpful to distinguish between a member’s ‘vocational’ job – i.e. the job they are employed to perform, and the job of being a co-op member. Some co-ops have devised a ‘Member Job Description’ which identifies the responsibilities as well as the rights of co-op membership. For example, the responsibility to acquire or perfect ‘co-operative skills’ such as being a good communicator, participating actively in meetings, being assertive, understanding how to reduce tensions in the workplace and deal competently and effectively with any conflicts that arise.

Recruitment

Before advertising for new co-op members you need to be clear what the job entails so you can write a job description and person specification, which can be used to write adverts for local media and community newsletters.

The job description should include a job title, all the tasks and responsibilities of the post, and support and supervision details. The person specification describes the essential and desirable qualifications, skills, knowledge and experience you are looking for.

You will also need to think through how the new recruit(s) will fit into the organisation. Where will they work? Is there a need for additional tools, materials or equipment? Who will show them the ropes and help them to integrate? Are they to be employed part-time or full-time? What about payroll, insurance, health and safety?

When you have thought through all the implications of taking on new staff and you have the job description and person specification written, you will be ready to advertise the post, either through informal or formal channels.

Recruitment can be an expensive process, so be sure to use all the informal channels you can find, bearing in mind that in order to ensure your co-operative is engaging with all sections of the community you will need to place adverts in a wide range of media and social media.

Induction of new recruits is vital to maintain the co-op’s principles and ethos. If induction is ignored or inadequate, new recruits may not understand the co-op’s mission or ways of working. As a result they will not be truly engaged, and when more experienced people leave, or when times get tough, the co-op can lose its way or get bought out.

Induction involves helping new recruits understand what a co-operative is, the background of the co-operative, how it was set up, its mission and how it functions. There may be some reading required, but try not to give the new recruit too much at once! Your website could have links to induction materials, to be downloaded as and when required.

It’s a good idea to appoint a mentor or buddy who will know where to get hold of induction documents as and when the new recruit is ready. They could also lead a guided tour of the premises on their first day, including being introduced to everyone and being shown the toilets, tea making facilities, where to take lunch, bike parking facilities and anything else they need to know.

Finally, away days are useful for the new recruit to get to see and participate in activities involving everyone in the co-op. Away days can be an exciting opportunity to appreciate the scope and extent of what they have become involved in, and what the opportunities are for personal and career development, as well as lots of fun.

Induction reading could include:

- Co-op background and history

- Mission statement

- Constitution

- Business plan

- Policies and procedures in case of

- Emergency, accident or fire

- Customer complaint

- Organisational structure

- Meetings standing orders, ground rules and timetable

An away day is an event, often held away from the work premises, where members get together to celebrate achievements and plan new projects. With plenty of opportunities for fun, good food and getting to know each other, such events can really help to integrate new recruits into the team. You might want to try some co-operative games or the exercise below is useful and often an eye opener.

If an away day is too expensive and time-consuming for your co-op, there are a variety of other ways in which you can make spaces for people to engage socially, including eating together or brief social events after work. Whatever way you choose, try to get everyone together frequently. When people understand something about each other’s backgrounds, hobbies or likes and dislikes, team working improves and conflicts are easier to address.

Group timeline and stories

- Everybody arranges themselves in line according to how long they have been a member of the co-op

- Divide them into groups of 4 or 5, with ’newbies’ in the first group through to ‘old timers’ in the last

- Ask each group to talk amongst themselves about what it was like when they joined, remembering how things were in the early days – perhaps a funny incident or a disaster that they somehow survived

- Get the newbies to talk about how it was for them joining more recently

- Then each group shares their stories, as much as they want to

- This exercise can be revelatory and is an empowering group experience

Member (or personal) reviews

Member reviews provide members with support as well as providing a structure for accountability. Any kind of business with employees needs to carry out regular staff reviews. But it’s how it’s done that interests us here. In a co-op you will often find a flatter, more democratic organisation. You may find that all the employees are directors and you may find a variety of organisational structures – management by General Meeting or Management Committee, which may have delegated powers, or be representative of different teams or departments.

So we are not looking for a ‘one size fits all’ solution. In any business an employer worth their salt will hold regular employee reviews so that employees have the confidence that they are doing a good job, and the employer gets to know when people need training, or need new software or equipment, or when they need to recruit more staff, or give more hours to existing staff.

So in a flat, democratically-managed workplace, it’s just as important to have this information, and there are a variety of ways you can do that. But first of all it’s worth considering why we do it and what’s likely to happen if we don’t:

Why do it?

- It provides security for members – they know that they are doing the right things, in the right place at the right time. They know when they have done a good job

- It gives you an opportunity for praise

- It makes people feel valued

- You can identify when people are under-performing or struggling

- The team knows when a member needs training or needs a new app or software

- The co-op is informed that there is a need to recruit additional staff or provide existing staff with additional hours. Or that a job description needs to be altered, or split between two people

- It allows you to match expectations with reality

- It provides a career path

- It provides useful information for individual members, and can be the basis for a personal development plan

What happens if you don’t?

- There’s a cost to the business of ‘hiring and hiring’ (i.e. finding another role for an under-performing member and recruiting a new member for the post); increased staff turnover; increased cost of new member induction

- There’s a cost to member morale: “if they skive off why can’t I?”

- Frustration can build up if people don’t get feedback

- A lack of feedback prevents people growing and developing their skills

- People bottle things up – leading to grievances

- A lack of engagement can cause long term dissatisfaction

- There’s a cost to the co-operative culture: new members will see the contradiction between what you say and what you do; it will undermine the co-op’s mission

Here are some approaches:

| Type of review | Approach |

|---|---|

| Member review | Members identify key elements and skills involved in their job description, then carry out a preliminary reflective review using a scoring sheet. A second review is carried out with a colleague who challenges the individual, helping them to clarify their answers. The next step is to identify personal improvements, training requirements and personal targets for creating a personal development plan. |

| Co-op member and job competencies review | This approach identifies and separates out ‘co-op member competencies’ from ‘job competencies’. This results in a ‘Member Agreement’ (a list of co-op member competencies that every member must fulfil). Job competencies are the vocational skills, knowledge and experience required for specific roles, and should be attached to each job description. Members and probationary members are assessed either by a colleague or sub-committee, and lack of competencies form the basis of training plans and new member induction procedures |

| Buddy system | Each member has a ‘buddy’ colleague to support them – a bit like a personal HR worker. Like the personal review above, the member carries out a self-assessment review and discusses it with the buddy. The buddy then presents it and their recommendations to the board or a personnel team. Action points are agreed by the co-op while the buddy monitors progress, so that it’s the co-op deciding improvement actions, rather than the individual member. |

| KPIs / personal targets | Members are allocated Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) relating to their job role. Regular review meetings are held to assess performance against KPIs and discuss related issues. KPIs may be allocated to teams instead of individual members. |

| Personal review (peer listening process) | There are three elements to this process: 1. Annual: review of business plan and job descriptions 2. Monthly: ‘group listening’ session. The whole group listens whilst two members receive feedback, based on a ‘Stop – Start – Continue’ model. Feedback recipients have the option of offering a response at the end of the session, and of offering a further response at the beginning of the following month’s session. 3. Monthly: each member has a one hour meeting with a buddy, reflecting on the previous group listening session, and any lessons learnt. |

Member review with support of the personnel team | Co-op members receive a questionnaire from the personnel team every 18 months. The purpose of the questionnaire is for members to review each other’s work. Each member is expected to complete a review of 75% of the membership. The feedback is anonymised and sent to each member who then meets with the personnel team and the training team to discuss how they feel about their workload, what training they might need, and if they have other skills which the co-op might benefit from, amongst other things. This information is fed into a training and development plan |

The way you approach designing your review process will depend upon your co-operative culture, the sector of the economy you are working in, your organisational structure, its age and its size. Whichever way you do approach it, bear in mind that this is not a policing exercise. It’s a way of providing members with feedback on their performance – praise for a job well done or support for a member who is over or underworked, or who needs training or additional resources. It’s a way of helping the co-op to move forwards, responding to new challenges and accomplishing its mission.

Before implementing a member review process:

- Work out what’s right for your co-op, be clear about why you’re doing it and how you will measure success

- Start small – is there a team that would be prepared to pilot the chosen approach?

- Run a pilot, then have a retrospective look at what happened: What worked? What didn’t? Can we do better next time? Keep on tweaking and adjusting till you’ve got it right.

- Then the next question is how will you scale it to the whole co-op? Can you use the early adopters as champions of the pilot procedures?

Participative strategic planning

Participative strategic planning is a means of engaging all members in planning the future direction of the cooperative business. In this way we can avoid conflict caused by lack of information or misunderstandings about “how we do things here”. It’s strategic planning done in a co-operative, collaborative and participative way.

Strategic planning is a way of coping with change and planning for the future. It aims to accomplish three tasks:

- To explore and clarify direction for the medium to long term, identifying desired outcomes

- To select broad strategies that will enable the co-operative to achieve those outcomes

- To identify ways to measure progress

Co-operatives use the process to build member commitment by involving them in the creation of the plan, but how you go about it will depend on your co-op’s structure, how long you have been established, your economic sector and the complexity of your business.

It’s helpful to clarify the language of strategic planning before you start – at least so that everyone can agree a common understanding:

Strategic work is about where you want to go. It’s about the long term and involves setting aims and objectives, goals and outcomes – or draining the swamp?*

Tactical is about how you’re going to get there, agreeing a route or a map. It’s more reactive and perhaps opportunistic, involving setting milestones towards the achievement of goals and organising timetables, action plans and rotas.

Operational is about the journey. It focuses on the short term day to day outputs, crisis management and fire-fighting – or fighting the crocodiles?*

*i.e. maybe rather than wasting time and resources constantly fighting crocodiles, we should take time out to drain the swamp?

Some key questions for strategic planning:

- Are your co-operative vision and values clear, agreed and owned?

- How well do you understand the market? Is it growing, shrinking, or flat-lining?

- How well-informed are you about suppliers and competitors?

- How fit is the co-operative organisation? Purring along nicely or a bit bumpy?

- Are members ready to act?

Strategic planning – beyond the systems approach

It is increasingly recognised that existing management tools are inadequate, since they are based on ‘systems’ thinking, which assumes that organisations are like machines that can be controlled by managers ‘pulling levers’. Instead, Ralph Stacey describes what happens in organisations as ‘complex responsive processes’ with high participation and constant change. He sees an interplay of human relationships and communication where people create and are created by the organisation, and where no one can plan or control this interplay.

Tools and techniques for participative strategic planning

Agile methodology is an approach to business planning based on techniques typically used in software development as a response to unpredictability. In contrast to traditional project management, with its sequence of defined aims – market research; product development; market strategy; implementation – the Agile approach is repetitive and incremental, with activities blending into several iterations and adapting to environmental reality.

Risk Analysis is a different approach, involving looking at all the risks to your co-operative business and quantifying them in a table according to:

- (A) How likely is it to occur?

- (B) What impact would it have on the business if it did occur?

- (C) What can be done to prevent the risk from happening?

- (D) If it does happen anyway, how could we minimise the impact?

You then multiply (A) by (B) to get a rough and ready way to prioritise action. Columns (C) & (D) provide a framework for objectively reviewing ideas for prevention of risks or at least potential damage limitation.

Appreciative Inquiry is a more positive, glass half-full approach. It involves four stages:

- DISCOVERY Focus on what’s working, build on success. What are our strengths? What do we enjoy? What do we want to do more of?

- DREAM Use our strengths and what we want to do to create a shared vision of the future – what might be?

- DESIGN Co-create a design to make it happen, based on our values and principles

- DELIVERY What will be? Sustain the vision through empowering people, learning, adjusting, improvising.

When faced with a totally new situation, we tend always to attach ourselves to the objects, to the flavour of the most recent past. We look at the present through a rear view mirror. We march backwards into the future.

Summary

Chapter 4 explored the tensions that can arise as a co-operative develops. It identified tools, techniques and approaches which will help as the co-operative experiences growth and change.

- We reviewed techniques for managing change

- We highlighted the need for written policy and procedures to address issues such as recruitment, induction and appraisals or personal reviews.

- Lastly we provided a summary of tools to facilitate participative strategic planning