Communication skills

Introduction

From conflict to co-operation aims to help co-operatives not only to deal with conflict when it arises (Chapter 1), but also to avoid unnecessary conflict by:

- Improving communication skills – this Chapter

- Improving meetings and decision-making – Chapter 3

- Managing change caused by organisational growth and development – Chapter 4

- Clarifying the roles and responsibilities of the board – Chapter 5

In this chapter we start by outlining some basic communication concepts. We then look at steps we can take to improve communication, including avoiding misunderstandings that arise from assumptions based on cultural or gender differences. We return to the importance of being assertive for good communication, and how the co-operative will benefit from maximum participation by members.

Good communication skills are important in all areas of life, but in a co-operative enterprise it is vital that everyone knows how to communicate effectively, since the success of the enterprise relies on the shared skills, experience and knowledge of all the members.

Communication skills are important in day-to-day working with colleagues, during meetings, in writing progress reports for members and when promoting and selling the activities of the enterprise. They can help to ensure that information shared is concise, accurate and timely.

Who speaks sows, who listens reaps.

What’s really happening when we communicate?

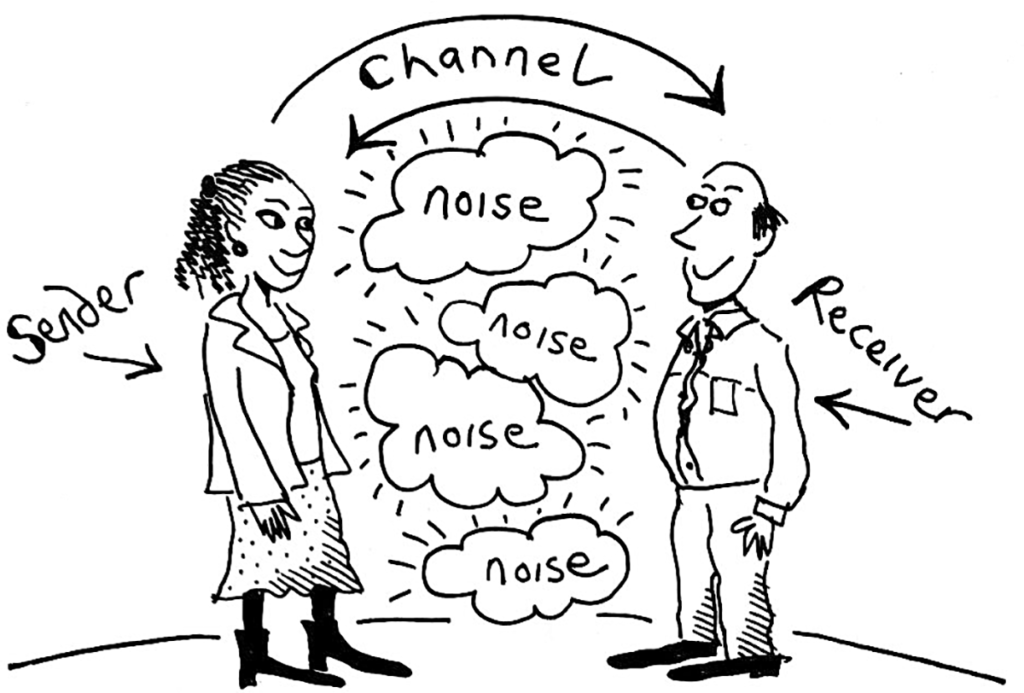

Communication can be described as a two-way process of sending and receiving messages.

Those messages are sent and received through a channel. The channel can be the air between us, a page of a book, a newspaper, magazine, letter or report, loudspeakers, a phone earpiece or a computer screen.

‘Noise’ can occur in the sender, in the receiver or in the channel. ‘Noise’ means anything that gets in the way of the receiver understanding the sender’s meaning.

I know that you believe you understand what you think I said, but I’m not sure you realize that what you heard is not what I meant.

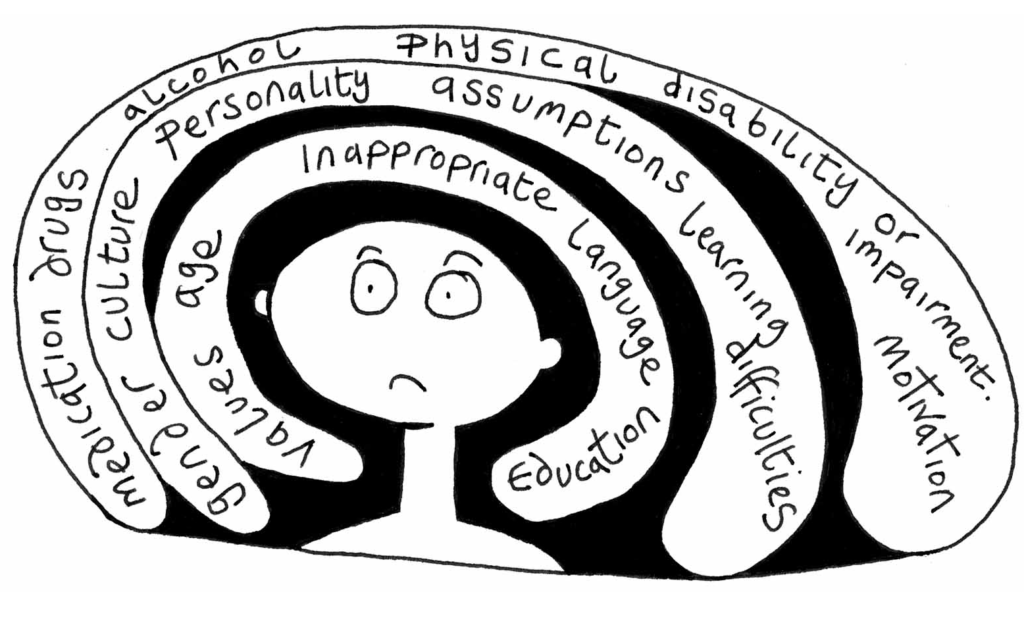

In the sender or receiver (i.e. the people) the noise might be:

- Differences in language, education, age, gender, culture or personality

- Ignorance or unchecked assumptions

- Prejudice or racism

- Lack of awareness of different needs

- Medication, drugs or alcohol

In the channel, examples of noise could include:

- Actual physical noise

- Poor page layout

- Typeface too small

- Poor screen design

- Printer ink cartridge running out

- Illegible handwriting

- Mumbling or shouting

So the essence of being a good communicator is to reduce noise, wherever it occurs – in the sender, in the receiver or in the channel.

Reducing noise in the sender

If you have the job of sharing information, whether speaking during a meeting (face to face or online), sending an email or writing a report, the issues are the same.

Remember that in order for as many people as possible to hear what you want to say, you need to think about what possible noise there might be which could prevent your listeners or readers from hearing or understanding what you mean. In order to do this, think about the message you are sending. It should be structured, clear, concise and congruent.

It’s good to take responsibility for your message by using ‘I’ or ‘My’, (only say ‘We’ if you are speaking on behalf of a group or team). If you are speaking to a large group, check that everyone can hear you. Many public buildings have induction loop systems for deaf people or those with hearing loss. If you are organising a public meeting to promote your activities choose a venue with good facilities and consider hiring a signer.

Structured: Try to think about what you want to say, so that your message has a logical beginning, middle and end.

Clear and concise: Avoid any ambiguity and keep the message as short as possible.

Congruent: Know your audience and choose language examples and illustrations appropriate for them. Also your body language should correspond with your message – for example, be careful not to smile inappropriately if your message is a serious one.

However be aware of neurodiversity*: for some people, conveying or reading appropriate body language or facial expressions can be a real challenge.

* Neurodiversity refers to the different ways a person’s brain processes information, such as autism or dyspraxia.

A good way of reducing misunderstandings is to let your audience know that you welcome questions, comments and feedback. If you are giving instructions to an individual or a small group, you can ask them to repeat what you have told them in their own words.

Written instructions can be useful back-up but only give them out after you have finished, otherwise people will try to read them while you are speaking and they won’t be listening. In a written document, if you use acronyms or jargon, provide a glossary.

Reducing noise in the receiver

Noise can also exist in the listener or reader. Many people, perhaps especially the talkative, find it difficult to listen. The Greek philosopher Epictetus said “We have two ears and one mouth so that we can listen twice as much as we speak” – or as a talkative young co-operator once said: “Big mouth needs big ears”.

To ensure that you have understood, it’s helpful to ask questions or, if appropriate, repeat what you have heard back to the speaker in your own words, to check you have heard it correctly. You should say if you can’t hear properly, or ask for written notes, a glossary or an explanation of acronyms.

Active listening can help us to identify what is really happening when we are apparently listening to another person. For example, we are often thinking about our response to what the speaker is saying before they have finished speaking, so we are not giving them our full attention. Active listening can make listening more effective and thereby eliminate noise.

Active listening exercise

In pairs (a speaker and a listener) take it in turns to speak for 2 minutes on any topic. The listener should practise active listening. The rules for active listening are:

- Pay 100% attention to the speaker.

- Do not speak, except for statements mirroring what the other person has just said, with the aim of checking that you have understood.

- Use body language to indicate that you are listening.

- Make eye contact (but not to the extent that it feels unnatural).

- After 2 minutes, swap roles.

Finally, feed back by sharing how it felt. For the speaker it may have felt uncomfortable speaking for 2 minutes without being interrupted. It rarely happens in day to day life. For the listener, having someone paying complete attention to them might be a revelation.

This exercise can be used in a communication training session, in a difficult meeting to ensure that everyone feels they have been heard, or by a third party facilitating a situation of tension or conflict in the workplace.

Reducing noise in the channel

The channel is the means by which the message is transmitted. There are a variety of different ways in which noise in the channel can prevent the message being understood. We talk about physical arrangements for meetings in Chapter 3. However, it is worth mentioning that physical discomfort – e.g. heat, cold, draughts, thirst, hunger, uncomfortable seating – can all affect concentration and thus create ‘noise’.

If you need to pass on information verbally, choose a place and time where you will not be interrupted or drowned out by actual physical noise, and arrange seating so that everyone can see and hear you. If you are delivering training, remember that most people’s attention span is no more than 20 minutes, so intersperse presentations with time for questions and activities.

When the channel is paper or an electronic document, pay attention to layout. Good design with plenty of blank space and avoidance of too many different typefaces can help minimise noise. Diagrams, illustrations and cartoons can often convey your meaning more effectively than words.

Poorly designed web pages create noise that can make it difficult for users to access information. It’s important to use recognised standards for website design so that, for example, people who are blind or partially sighted can use screen readers to access the information.

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) develops standards and guidelines to help everyone build a web based on the principles of accessibility, internationalisation, privacy and security. https://www.w3.org

In order to save on transport costs and reduce carbon footprint many co-operatives hold meetings online. Online apps such as Zoom, GoToMeeting or MS Teams offer different methods for communicating and sharing information including live chat, document sharing and collaborative online whiteboards.

With all of these methods, the same skills are required for effective communication: good listening skills, asking for and giving feedback, thinking about structure and removing potential for ‘noise’.

Obstacles to communication created by cultural or gender differences

Cultural

The expression ‘cultural’ has different meanings. We are using it here to mean a set of shared attitudes, values, goals and practices belonging to a group of people.

Different cultural backgrounds can create significant ‘noise’ in communications – being aware of them is the first step to diminishing their power as obstacles to effective communication. We cannot expect to be aware of all the aspects of other cultures that might become obstacles to communication, but we can ensure that everyone in the co-operative is aware of the impact of such obstacles.

Examples of noise created by cultural differences include:

- Gestures – a thumb and index finger making a circle means OK in the USA, money in Japan and is an insult in Brazil.

- Eye contact – can be offensive in some cultures but indicates reliability and honesty in the UK.

- Personal space – in some cultures, people are accustomed to standing or sitting closer to each other than in others, and people may touch your arm or your hair – not as a sign of personal intimacy, but as a natural part of their way of communicating

Rice University in Houston, Texas provides an excellent online tutorial aimed at improving cross cultural communication.

Gender

Gender differences in communication styles can become obstacles to effective communication. In ‘Talking from 9 to 5: Women and Men at Work’ Deborah Tannen says that men and women typically use different conversational rituals and styles – and when these are not recognised, misunderstandings can arise.

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

Tannen describes how women’s conversational rituals often include apologising, or adopting a self-deprecating tone in order to maintain equality or offer reassurance. Women are often told not to apologise – it is seen as putting oneself down. But for many women (and some men) saying “I’m sorry” isn’t meant as an apology, but as a ritual way of restoring balance to a conversation, an expression of understanding or caring about the other person’s feelings.

When an apology is offered as an acknowledgement that something has gone wrong (maybe it’s not clear who is at fault), it is often the first step in a two-step routine whereby saying “I’m sorry” means taking half the blame, and expecting the other person to take the other half.

Admitting fault can be experienced as taking a one-down position, so when both share the blame it is a mutual face-saving device – a courteous way of not leaving the apologiser in the one-down position. However, if one person doesn’t understand the ritual, and accepts the apology, the other could be left feeling resentful and frustrated. Like all conversational rituals, ritual apologies only work when both parties share assumptions about their use.

Conversational styles common amongst men include banter, joking, teasing and playful put-downs. Some men will try not to end up in a ‘one-down’ position in any conversation, which can sometimes be experienced as hostility.

Deborah Tannen points out that no one style or ritual is better. Problems arise when styles differ and when rituals are not recognised. She does not suggest that women or men change their conversational styles or rituals, only that we recognise them and become more flexible.

Assertiveness

As we saw in Chapter 1, assertiveness means knowing your own mind and standing up for yourself, without imposing your views and opinions on others. It is more likely to lead to effective communications since it is another way of minimising ‘noise’.

Body language

It’s important to be aware of what messages your body is conveying. This awareness is part of being assertive. However, it can be tricky for some people to do these things and they might inadvertently be conveying unintended messages. For example it can be challenging conveying appropriate facial expressions for some autistic people, or regulating speech volume and clarity for some dyspraxic people. Others need to be aware and listen for that.

| Do | Don’t | |

|---|---|---|

| Breathing | – Deepen your breathing and calm yourself prior to a confrontation | – Forget to breathe |

| Posture | – Have an upright posture – Make sure you are at the same level (i.e. both standing or both sitting) | – Slouch – Stand too near or too far away from the other person |

| Eyes | – Keep your gaze relaxed – Maintain eye contact, but note what was said earlier about eye contact in different cultures | – Avoid looking at the person you’re speaking to |

| Mouth and Voice | – Relax your jaw – Smile if it is appropriate to do so – Speak clearly and slowly so you can be heard – Watch the tone, inflection and volume of your voice | – Whine, shout or mumble – Convey sarcasm through the tone of your voice |

| Gestures | – Use gestures that help you express what you want to say – Make sure your body language is congruent with your words | – Cover your mouth with your hand – Play with your hair or jewellery – Put your hands on your hips or fold your arms –Shift from one foot to the other |

Giving feedback assertively

Being assertive can really help us in difficult situations such as giving negative feedback. Talking to a colleague about their unsatisfactory work is difficult. Many of us shy away from it or let it build up until we make a remark which is angry or resentful. It’s better to deal with the situation assertively.

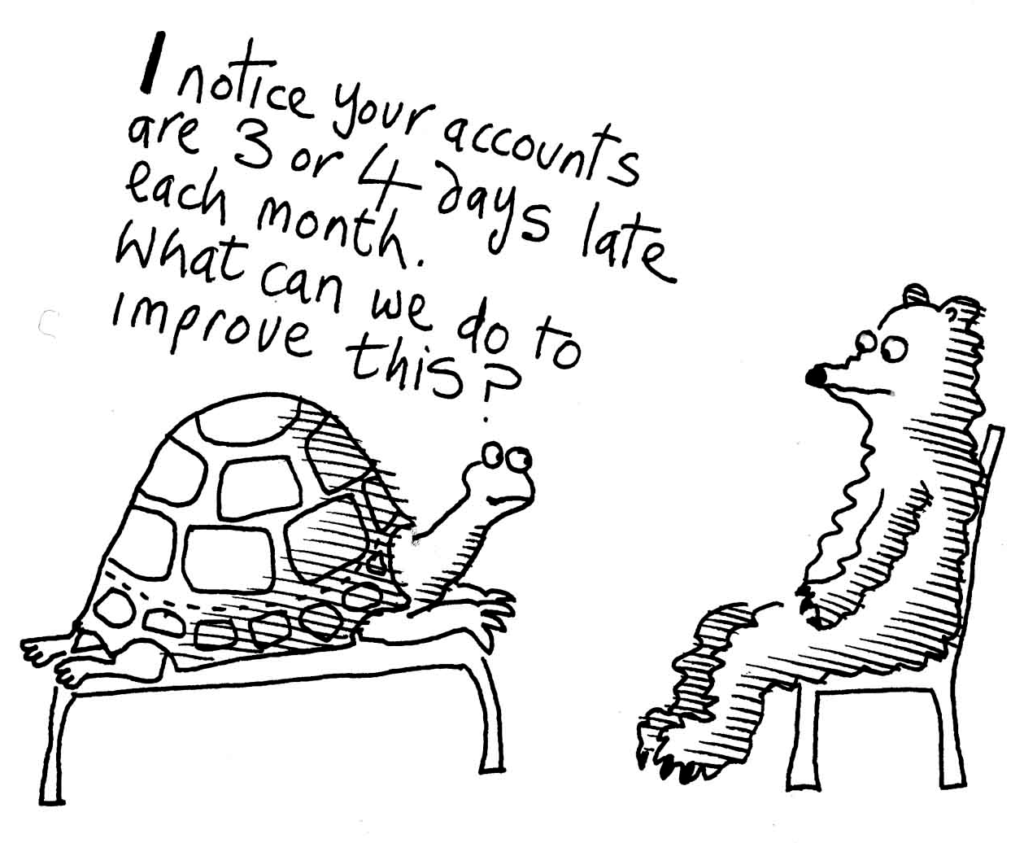

The first step is to check that your goal is clear in giving the feedback. It is not just an end in itself. The aim is to change some aspect of the way your colleague carries out their job. Let’s take the example of a colleague whose job it is to bring you monthly accounts:

They are never on time with them and you have to keep chasing them up. Your aim is to receive the accounts on time, so you can do your job.

- Rights: You have some rights in this situation. You have the right to expect people to perform their work adequately. They have rights too. They have the right to expect you to behave in a way which doesn’t put them down, attack them or make them look small. Their mistakes do not give you the right to behave aggressively.

- Be specific about the change you want. Raise the problem at the time. Try not to let it build up. Choose a suitable time and place, away from other colleagues: “I’d like to talk to you about the accounts”.

- Talk about behaviour you can see. Express your feedback in a factual form: “I notice the accounts are three or four days late each month”. Don’t make personal statements which could be seen as an attack, such as “You’re so sloppy” or “Your attitude is too laid back…”

- Make sure you are speaking for yourself by using ‘I’. In this way you are speaking about your own feelings and perceptions, you are not attributing blame, you are being direct and honest about the effect the other person’s actions are having on you.

- Get a response to your feedback. This is about getting agreement. They might not agree. Ask: “Do you agree?” or “Have you noticed?” or “Why is this happening?”

- Ask for suggestions to bring about the change you want. “How could the timing be improved? What changes could you (we) make?”

- Summarise the suggestions to be carried out: “So, we’re agreed that in future you’ll…”

Following these steps means you’re more likely to get the change you want. You have been assertive, it’s more likely that you’ll get a response which isn’t aggressive or passive from your colleague and you’re building a better relationship.

Receiving negative feedback

When you’re receiving feedback it helps to behave in an assertive way as well. The following steps will enable you to take feedback without allowing it to become a personal attack and your response will be more considered and will help maintain or repair a good relationship with the other person.

The first step is to work out whether the feedback is justified. It might be justified, unjustified or just a put-down. You may need to think for a minute before you reply.

If it’s justified

For instance, you have arrived late too often. Whatever it is, you know it’s true and it does apply to you. It helps to use negative assertion. Negative assertion means acknowledging the truth in what your critic is saying: “Yes, I have been late quite a few times recently”. In doing this, you might feel less defensive and more accepting of yourself.

If it’s unjustified

You’ve received some feedback which is completely untrue. You could say “That’s really not true” or “I don’t accept that”. But say it with conviction, without apologising. Make sure your body language expresses certainty, not doubt.

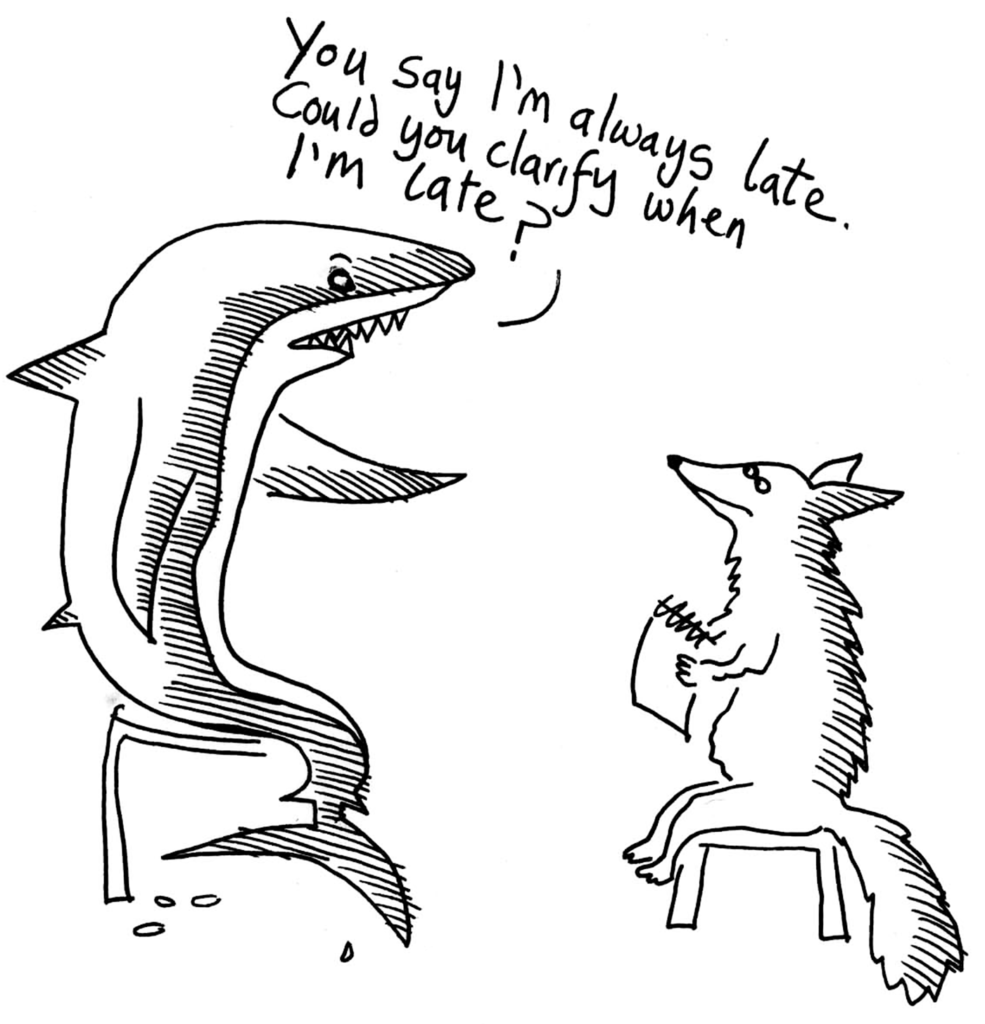

If you’re not sure

There might be some truth in it, but it’s an exaggeration. Ask for more information: “You say I’m always late. Could you clarify when I’ve been late?” If the accusation is vague or incorrect, you might say “Well, I have been late twice this month (acknowledging the truth), but it’s not true to say I’m always late.”

Put-downs

If you’re feeling put down by a remark, the assertive way to deal with it is to say that you feel put down, and what your reaction to it is. For example, you’ve been told in a jokey way that you have no sense of humour. You might say: “I found what you said hurtful” adding “and I’d like you to stop”. Sometimes you only realise afterwards that something was a put-down. It’s assertive to confront the person later in the same way as above.

My Rights

- I have the right to be treated with respect as an intelligent, capable and equal human being

- I have the right to express my feelings

- I have the right to express my opinions and values

- I have the right to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ for myself

- I have the right to make mistakes

- I have the right to change my mind

- I have the right to say I don’t understand

- I have the right to ask for what I want

- I have the right to decline responsibility for other people’s problems

- And I know that other people have these rights too

Re-framing

Re-framing is a way of stepping back from what someone has said, and changing the ‘frame’ (i.e. the set of assumptions that make up a person’s world-view), restating the message in order that they can hear the same facts from a different point of view.

It involves removing ‘noise’ (such as tone of voice, choice of words or mixed messages) from a communication. Re-framing can be used by mediators or colleagues to defuse charged emotions, to eliminate blame, accusations or insults or to identify common interests or common ground. A couple of examples:

“These problems do seem unresolvable, I agree and it looks like a waste of time to discuss them yet again, but we will waste even more time if we don’t find a way to resolve them.”

“You’ve said it can’t be ready by the end of the month. But how about if we bring in those two new recruits, to help you? It would be useful training for them as well.”

Re-framing is constructive when the goal is to empower the parties in a conflict, helping them to move towards a mutually acceptable solution. However, it is manipulative if the goal is to entrap the other person in your logic, exercising your power without respect for theirs.

We always hear about the rights of democracy, but the major responsibility of it is participation.

Participation

High levels of participation in a co-operative can bring great advantages, since the enterprise will benefit from the wealth of skills, knowledge and experience of its members.

Encouraging participation can be difficult and time consuming – it sometimes seems easier just to decide by yourself what to do, without taking the trouble to consult others. However, this approach could present its own issues as others may question your right to decide for them. If you adopt some of the techniques suggested here, you can reap the benefits while avoiding the pitfalls and the co-operative will grow and develop as a result.

High levels of participation will improve decision-making, increase motivation and improve team working and information sharing. Participation means to take part, to be consulted or to be involved at some level in decision-making, goal-setting and planning. It can happen at various levels, and it is important that everyone understands in what way they are able to participate. It may be that clients or customers are consulted, which means that they will be asked their views, but will not take part in the ultimate decision-making.

Participation does not mean everyone getting involved in every decision – you’d never get any work done! It’s better to devolve decision-making to sub-groups or individuals, who are then accountable to the members. Those sub-groups and individuals should be aware of the limits of their decision-making authority and how they will be held accountable, and should then be left to get on with it.

Some decisions will need the agreement of everyone – decisions which affect most members, for example, or those involving large sums of money or which will impact on the co-op for years to come.

The facilitator (or chair) has an important role in ensuring everyone has an opportunity to participate in meetings. They should make it clear that everyone’s contribution is welcome and should avoid stating their position before others have made their contribution.

Participation can be encouraged in meetings by good planning and the use of a variety of tools. Some useful tools include:

- Cotton bud/matchstick debate – everyone has a number of cotton buds or matchsticks and must place a cotton bud in the centre every time they speak. Once the cotton buds are used up, they may not speak again

- A spoons debate – this works in the same way as the above cotton bud/matchstick debate. Everyone has a bunch of spoons and must place a spoon down on the table in front of them every time they speak – you can then see who has spoken most/least and reflect on that after the meeting

- People raise their hand when they wish to speak, the chair watches out for the order in which people raise their hand and ensures that people get to speak in turn

- The famous talking stick/conch shell – you may only speak whilst you are holding it!

Seeds for Change offer a wide range of tools for facilitation and increasing participation in meetings.

During a strategic planning process, the opinions of all co-op members can be collected through a questionnaire, analysed and organised by the board or a strategy sub-group, then discussed during a strategy event – perhaps an away day for the whole co-op. Participation in such an event can not only result in members feeling engaged and motivated, but will also generate excellent inputs for the development of the strategic plan.

Evaluation of meetings presents an opportunity for people to discuss how they feel about aspects of the meeting, including participation. Again, there are a range of tools available.

A quick and effective approach is to take a sheet of flip chart paper and draw a dartboard format, divided into sectors such as: preparation / decision-making / participation / interest / organisation / refreshments etc. The highest scores are near the middle of the dartboard, while nearer the circumference is a lower score. As they leave the room at the end of the meeting, everyone ranks each element of the meeting by marking the dartboard to indicate how satisfied they were with each element. Later you can easily see which areas people are happy with – and where you need to try harder!

- For more techniques for evaluating meetings see Chapter 3 Meetings and decision-making.

Summary

Chapter Two focuses on the importance of good communication skills for avoiding unnecessary conflict.

- We started by outlining some basic communication concepts

- We talked about the use of active listening and suggested an exercise

- We then looked at steps we can take to improve communication, including avoiding misunderstandings that arise from assumptions based on cultural or gender differences

- We described the benefits of being assertive for good communication, including an assertive approach to giving and receiving feedback

- Finally we emphasised how the co-operative will benefit from maximum participation by members