Conflict – where it comes from and how to deal with it.

Introduction

The From Conflict to Co-operation primer aims to help co-operatives to deal not only with conflict when it arises (this chapter), but also to avoid unnecessary conflict by:

- Improving communication skills – Chapter 2

- Improving meetings and decision-making – Chapter 3

- Managing change caused by organisational growth and development – Chapter 4

- Clarifying the roles and responsibilities of the board – Chapter 5

This primer is aimed primarily at ‘flat’, democratically-managed co-operatives, small or large. However, it will be useful for any groups working democratically.

Whilst it’s true that good governance will help co-operatives avoid many of the conflicts which can arise when a group of people work together, it’s also important to think about how we behave within the systems and processes of governance, using co-operative skills to improve communication, meetings and decision-making.

There are many types of co-operative enterprise, so some of the issues and problems we describe here may not apply directly to your situation, but they may help your thinking in general about how you address conflict in your co-operative.

Don’t be afraid of opposition. Remember, a kite rises against, not with the wind.

Governance: The systems and processes concerned with ensuring the overall direction, supervision and accountability of an organisation.

Conflict can be a tricky subject to deal with

We mostly shy away from conflict, afraid that it will damage our relationships with others or our confidence in ourselves. This is because we learn strategies for dealing with conflict mainly as children – perhaps in the school playground – and rarely have the opportunity to revisit or review those strategies, which may not be effective in adult life.

One way of looking at different responses to conflict is to see them along a continuum leading from avoidance – “run away!” – to confrontation, often based on violence or power relationships. Somewhere between these two extremes are strategies based on changing the subject – or confusing the issue – such as introducing distractions, irony or jokes.

None of these approaches is really satisfactory – if we run away we know we have not solved the problem; we have learned nothing and the next time we will probably run away too.

Changing the subject, or using comedy can work for a while – comedians sometimes say they learnt to be funny in the school playground as a technique for dealing with the school bully – but such a strategy is unreliable and does not solve the problem. Violent confrontation also has its downsides, such as a bloody nose or, if you win, enemies that may try to bring you down later.

However, confrontation does not have to be violent. It can be based on an assertive approach:

“I know I have rights and I acknowledge your rights – so let’s negotiate a settlement to this dispute that will suit us both”

In Chapter 1 we review different conflict resolution approaches – and we will find that this assertive, co-operative approach is the most satisfactory way to deal with major conflicts, since it involves people working together to find a solution everyone will commit to.

Conflict is part of life. It is evidence that there is a wealth of experience, knowledge and ideas in the group. So some conflict is inevitable and we need to know how to deal with it in a constructive way when it arises – that’s what this Chapter is about.

But much conflict is preventable and this is covered in detail in other chapters in the From Conflict to Co-operation primer.

Conflict in a co-operative – why does it happen?

Conflict in a co-operative arises for the same reasons it happens anywhere – people have different views about what to do or how to do it, they are subject to different pressures, they suffer emotions such as jealousy, fear and anger, and they compete to get their ideas accepted by the team.

In a co-operative enterprise, the organisation is created by the relationships between the participants, so maintaining mutual and respectful relationships is the basis for avoiding conflict. Below we list the main areas in which conflict can arise, with details of where to find tools, tips and techniques for reducing the potential for unnecessary conflict in other chapters in the From Conflict to Co-operation primer.

Competition over resources – people and money

It’s probably the first issue that comes to mind when thinking about conflict within an organisation. There will always be conflict over how best to use the different kinds of resources you have available. Let’s look at two examples – people and money.

People

You are a member of a wholefood worker co-operative, and chair of the board. You have arranged for a consultant to come in today to run a training session for the board on running effective meetings, including chairing skills. However, you are needed right now by your team to help with unloading a delivery which has come in late. If you aren’t there to help your team at the unloading bay that will hold things up in other parts of the business, in the short term. But if you don’t attend the training, the board will not benefit from your improved chairing skills in the longer term. How do you decide where you are most needed?

Two people facing each other cannot pull a rope.

Money

You have agreed to initiate two new projects this year, and you have set aside £5,000 to pay for them. However, on revisiting the budgets you find that costs have increased and you can now only afford to develop one of the business ideas. After consultation with all the members you find support for the two projects is evenly divided. How will you decide which project to implement?

There are no easy answers to these situations, but there are tools and techniques that will ensure whatever decision is taken will benefit from the support of all or most people. If everyone has been engaged in developing a strategy in which certain activities are prioritised, and in which everyone understands and supports, it will be easier to come to a decision on how you decide where you are most needed or which project is a priority. Also, if the people taking those decisions do so in a transparent way, and if there are opportunities for others to give feedback, what might be a controversial decision becomes more acceptable.

- See Chapter 3 on different decision-making approaches and Chapter 4 on participative strategic planning

Personalities and working style

Some people’s personalities or working style can make them challenging to work with. Many words have been written about dealing with ‘difficult’ people, people who are hostile or aggressive, unresponsive or silent, negative about everything, complaining all the time, know-it-alls or those who say yes to everything but never deliver. Behaviours such as these are often symptomatic of other underlying causes, which need to be identified and dealt with by the individual themselves. However, by improving communication skills – including assertiveness – and understanding how to deal with tension in the workplace, you will be able to get along with even the most ‘difficult’ people.

- See Chapter 2 for more on communication skills

Poor communication

Sometimes poor communication – or lack of communication – is a source of conflict. If people aren’t told what is happening, rumour and imagination will fill the gap. A game of ‘telephone’ demonstrates what happens when people aren’t kept in the loop. You can try this yourself:

Everyone sits in a circle. The starter whispers a short message to the person next to them, who then repeats (whispering) the message they heard to the person seated next to them, and so on till the message gets back to the person who first whispered it. Compare the two messages. This is what happens with rumour!

- See Chapter 2 for more on communication skills

Ineffective meetings and inappropriate decision-making methods

For a co-operative, meetings are a key management tool – and they need to be effective, decisive, short and amicable. Your regular team meetings should be no longer than two hours. A meeting that goes on for over two hours is unlikely to be productive unless there is a clear structure, lots of breaks, different ways for people to participate and a variety of presentation methods.

For an effective meeting, you need to:

- Encourage participation

- Understand the role of the chair

- Know how to use the agenda and take the minutes

It is important that everyone understands different decision-making methods and under what circumstances they are useful. If an inappropriate decision-making method is adopted or if a decision is agreed but not implemented for some reason, conflict may ensue.

- For more information on how to run effective meetings and different decision-making methods see Chapter 3

We can work it out. Life is very short, and there’s no time for fussing and fighting my friend.

Differences in skills, knowledge and work experience

It is useful if people are aware of each other’s skills, knowledge and experience. You may have done an initial skills audit, but perhaps people have moved on since then? What skills, experience and knowledge are there in the team now? Your members’ skills are a vital resource and an asset for the co-operative as well as for the individual – but only if they are recognised and acknowledged. If someone feels their skills are not recognised or valued it can generate resentment which could result in conflict.

Cultural and gender differences

In our diverse world, people we work with can be very different from us. We may be born and brought up in different communities, or in different towns or cities or different countries. We inherit different concepts about lifestyle, acceptable behaviour, relationships, education, work and so much more. All these differences are reflected in the language we use to communicate.

Language can be a crude means of communication. When a word is used by one person, it is weighted by their experience – how it was used by their family, teachers or school friends. When someone with a different life experience hears that word, it will be weighted with a different meaning, so they will hear something slightly different (or even very different) from what was intended. Such misunderstandings can lead to conflict.

Techniques such as active listening or asking for feedback can minimise ‘noise’ produced by cultural differences. It’s important to recognise people’s different cultural backgrounds. Cultural rituals around religion and hygiene can be misunderstood and prove controversial if everyone is not made aware of the needs (such as a quiet place for prayer at certain times of the day). The impact of culture on communication can also lead to conflict.

For example, in some cultures saving face can be more important to an individual than owning up to a mistake. Different cultures require different amounts of personal space, so someone might stand nearer to you or further away than you are accustomed to. It helps if you understand why. Even though there may be very different people involved in a co-op, everyone needs to be treated with respect in order for a good team-working culture to develop.

Sexist and racist language, stereotypes or behaviour have no place in a co-operative enterprise, and your diversity policy should make it clear that such behaviour will not be tolerated and that direct or indirect discrimination on the grounds of gender, race, disability, sexuality, religion or age is illegal.

Deborah Tannen has done some interesting work on men’s and women’s different conversational rituals, such as male banter and playful put-downs and female avoidance of boasting and downplaying authority. Tannen makes the point that neither set of rituals are superior, but that conflict can ensue when people don’t recognise a ritual and respond inappropriately.

- See Deborah Tannen’s website

- See Chapter 2 for more about how improving communication skills can reduce the likelihood of misunderstanding arising out of cultural or gender differences.

Racism and Anti-racism

Racism is discrimination against a person or people on the basis of the colour of their skin. (Equality Act 2010 definition of racism.) The concept was invented and perpetuated as justification for the enslavement of millions of Africans used as free labour by European economies on sugar and cotton plantations in the Caribbean and southern states of the U.S. It created the enormous wealth that enabled the industrial revolution in the UK and that we can see in the architecture of UK cities that benefited from the slave trade, such as Bristol, Bath, Manchester and Liverpool.

It is based on the erroneous belief that human beings can be differentiated according to a concept of ‘race’, and infers the inferiority of some groups of people and superiority of people of European heritage: “race is a social construct with no biological basis”, (The American Society of Human Genetics).

Nevertheless it is a powerful concept that still and increasingly results in inequity in modern societies. It’s not just about individual beliefs but it is also structural, in our institutions and legal systems. The concept became too useful – enabling some to profit enormously. When slave trading was abolished in the early 19th century, slave owners collectively were the richest people on the planet.

But can co-ops be racist? After all our 1st Principle states:

Co-operatives are open to all persons able to use their services and willing to accept the responsibilities of membership, without gender, social, racial, political, or religious discrimination.

Well, yes. As Jessica Gordon Nembhard states “Structural and institutional racism have cumulative effects and are woven into the fabric of our society. They are manifest in our preferences, attitudes, psyches and economic relationships as well as our social and political relationships. It’s insidious.”

- Her keynote address to the NCBA “Racial Equity in Co-ops: 6 Key Challenges and How to Meet Them” is well worth reading.

Anti-Racism

Trying ‘not to be racist’ is an exercise in futility. We can all exhibit racist behaviour. We can’t help it. We live in a racist society, organised on the basis of racist policies. However to call someone racist is just about the worst insult you can level at them. It brings to mind people in pointy hats and burning crosses, a repellent vision, but not the only way in which people experience racism. No-one is inherently racist – but we can identify racism in words, actions and policies.

We know that in the UK, Black people and other People of Colour endure the worst housing conditions, are more likely to suffer ill health, both physical and mental, have lower educational outcomes, higher rates of unemployment and have a higher percentage of their population incarcerated.

- Black Caribbean pupils in England are three times more likely to be permanently excluded than white British pupils.

- In the UK, Black people are ten times more likely to be stopped and searched by the police than white people.

- More than half the inmates in prisons for young people in England and Wales are from a black or minority ethnic background while this group makes up only 14% of the UK population (MP David Lammy in the Guardian 2019)

There are two possible reasons for this cruel and unjust situation: either some groups are inferior to others, or there is racial discrimination in housing, health, education, employment, policing and legal system policies. Believing the former is a racist belief, believing the latter is an anti-racist belief. The only alternative to ‘trying not to be racist’ (i.e. doing nothing, and thus perpetuating racism) is to be anti-racist.

Anti-racism is rooted in action. It’s the process of actively identifying and opposing racism. Calling it out when we see it, educating ourselves about how Black people and other People of Colour experience it, recognising and identifying white privilege, waking up to the realisation that what white folk regard as ‘the norm’ (in a work situation, for example) may not be the norm for others.

Can a co-op be anti-racist? I’m not sure the journey is ever over, but it can for sure have a commitment to anti-racism, evidenced by its policies, procedures, actions, and in its culture.

Further reading and useful links:

- www.theguardian.com/world/2021/sep/19/no-more-white-saviours-thanks-how-to-be-a-true-anti-racist-ally

- www.waterstones.com/book/how-to-be-an-antiracist/ibram-x-kendi/9781847925992

Unclear roles and responsibilities

A common source of conflict is a lack of clarity between the role of board and the roles of the members. This is especially so when, in a fledgling co-op, it is the same people fulfilling both roles! It’s important to differentiate the role of the board from that of the day-to-day running of the co-op. Depending on your organisational structure this body may be called the ‘Board of Directors’ or the ‘Management Committee’. For the sake of simplicity we have called it ‘board’ in these chapters.

- See Chapter 4 Organisational growth and development and Chapter 5 Role and responsibilities of the board

Lack of written policies and procedures

How will a new recruit know what action to take under certain circumstances, if policies and procedures are not written down and clearly available? In the early days, it will all be in someone’s head, or people working in close proximity can ask each other what should be done. But eventually, when the enterprise grows and new people are taken on, the whole team must have easy access to this information. Policies also need to be reviewed and updated regularly and everyone should have an input into this process.

- See Chapter 4 Organisational growth and development

Power relations – them and us

When a co-op grows from two or three people to a group of six or more, it is very easy for the founders to assume that the way they have always done things will be adequate and appropriate for the larger group. In a small group information is shared informally, maybe outside work in a social setting, but problems will arise if systems are not formalised so that new recruits can access information easily. An effective induction programme will help new recruits feel part of the enterprise more quickly and subvert any growing ‘them and us’ dynamics.

- See Chapter 4 Organisational growth and development

Ignorance, insecurity, fear

Finally, conflict can arise out of people’s ignorance and fear. If people are not made welcome, if they do not understand what is required of them, or if they find themselves in a situation where they feel exposed or vulnerable, they may act in ways which can generate conflict.

See Chapter 2 Communication and Chapter 4 Organisational growth and development

How to manage inevitable conflicts

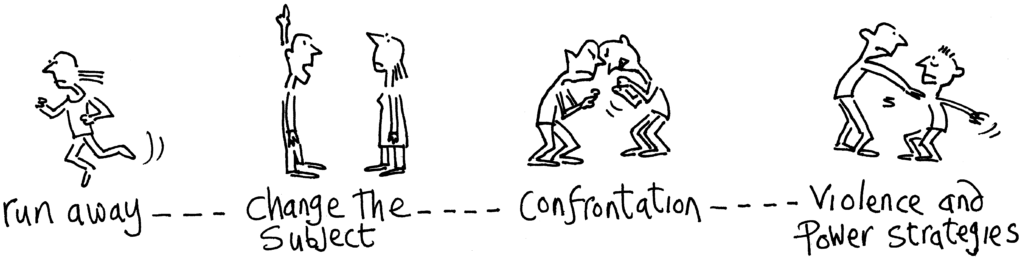

The following five different approaches to resolving conflict show the dynamic relationship between achieving personal goals and maintaining good relationships with others.

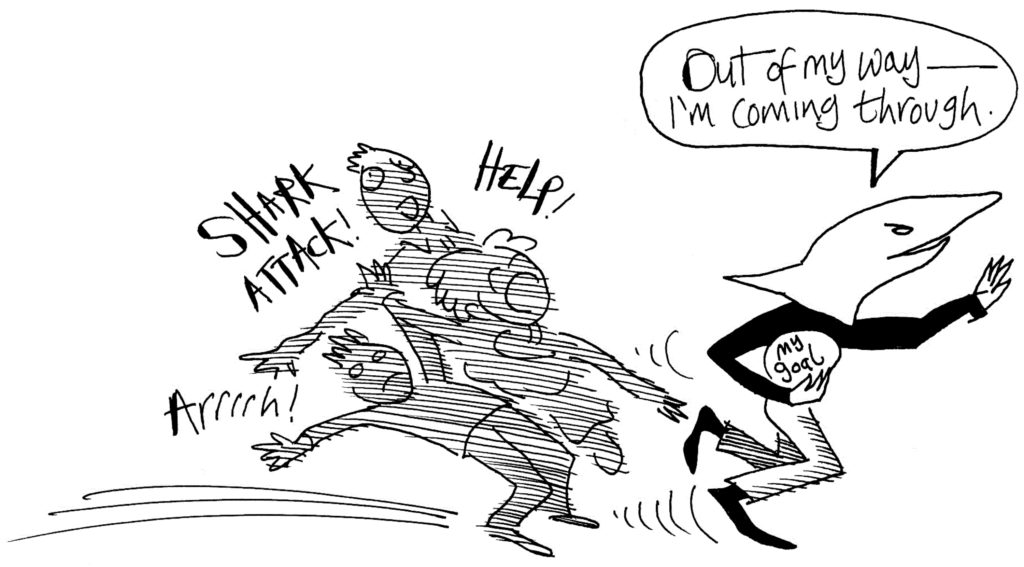

- Competition: Aiming only to achieve my goals

- Accommodation: Aiming only to maintain a good relationship with the other person

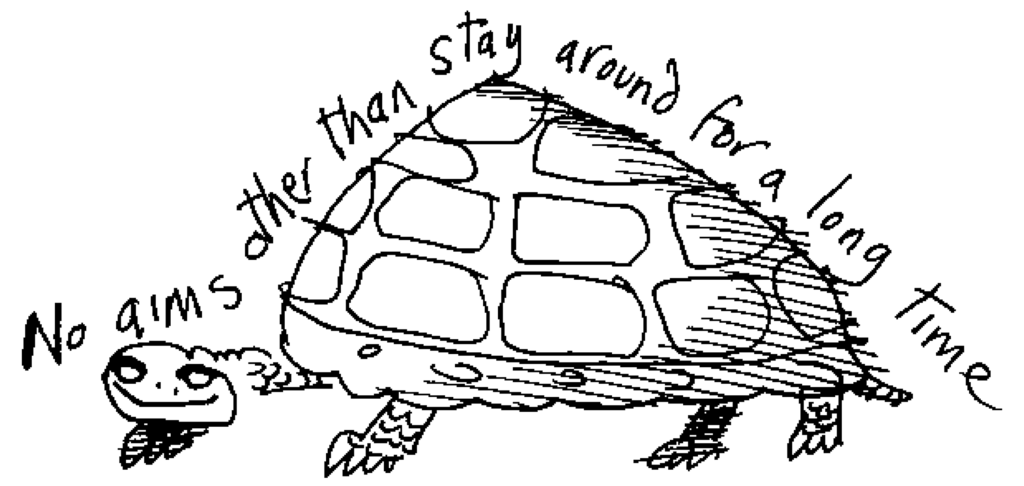

- Avoidance: No aims at all other than survival

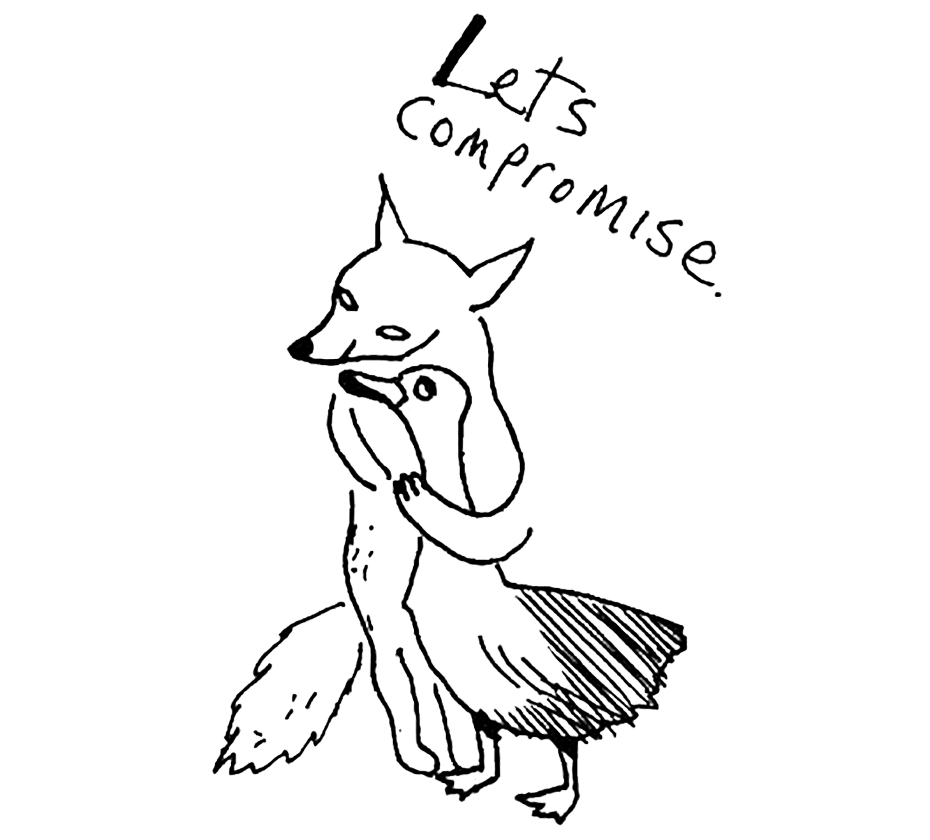

- Compromise: Aiming to balance achieving my goals and maintaining good relationships

- Co-operation: Aiming to achieve my own goals at the same time as maintaining good relationships

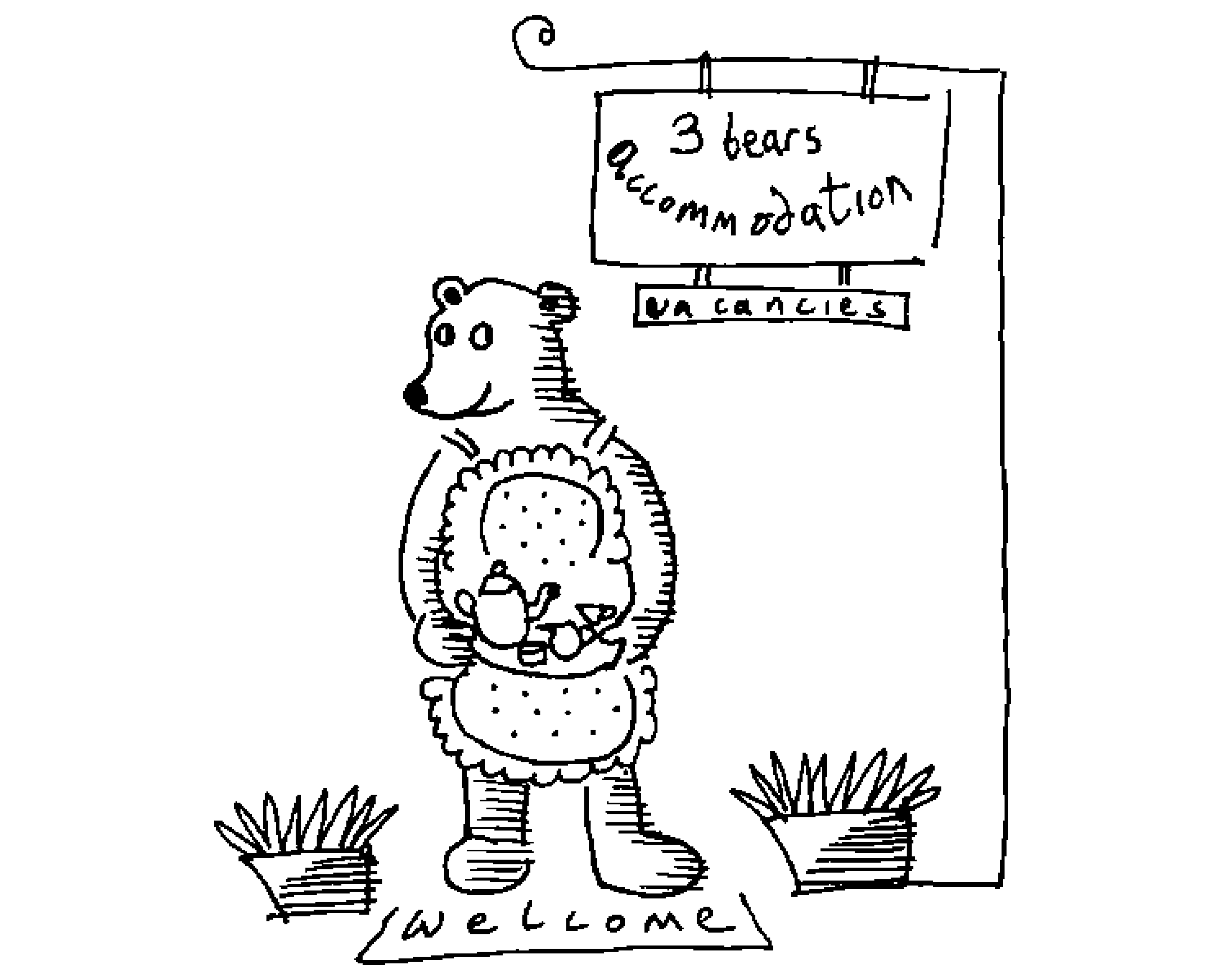

The illustrations on this page and overleaf are adapted from conflict strategies game in Johnson, D & Johnson, F, 2000 ‘Joining Together: Group Theory and Group Skills,’ Allyn and Bacon.

Competition

When we focus entirely on achieving our own ends at the expense of our relations with others.

This approach is aggressive and uncooperative, but in extreme situations may be called for to protect the vulnerable.

Accommodation

When we believe that good relationships with others are more important than our own needs.

This approach is unassertive and powerless, but could also be described as selfless and focusing more on your responsibilities than your rights.

Avoidance

When we are neither achieving our own goals nor building good relationships.

This approach is passive and uncooperative but could also be described as a tactical withdrawal.

Compromise

When we work out ways in which we can achieve our own goals without confrontation, using techniques such as splitting the difference, rolling a dice or taking it in turns.

Compromise is useful in situations where neither party is invested in a specific outcome, however it can lead to manipulative behaviour.

Co-operation

When we work together with the other party, investigating ways in which we can both win, thus achieving our goals at the same time as building good relationships.

This approach works towards win/win solutions, it is assertive and co-operative.

There are situations in which each of these styles is appropriate and they all have their advantages and drawbacks. However, we all have our habitual responses to conflict situations, so it’s helpful to identify what they are, and to recognise that other styles may be more appropriate.

- See Cooperantics How to identify your own habitual response to conflict

Techniques of principled negotiation

Of all these attitudes towards conflict resolution, it is the co-operative and consensual approach which provides the most satisfactory solutions to disagreements over major or long term issues. Because people have been consulted and involved, they will feel most able to commit to agreements arrived at through consensus. However, it is time consuming, so may not be appropriate for more trivial or short term issues. Also, it is not always easy and can lead to Groupthink.

Groupthink happens when it’s more important for an individual to feel part of the group than to consider alternatives which may not meet the approval of others.

A useful set of techniques for resolving conflict using a negotiated approach has been developed by a team based at Harvard University. In their book Getting to Yes, authors Fisher and Ury describe the techniques of Principled Negotiation, based on four steps:

- Separate the people from the problem

- Focus on interests, not positions

- Invent options for mutual gain

- Insist on using objective criteria

A good half of the book focuses on ‘Yes, but” questions – “What if they are more powerful? What if they won’t play? What if they use dirty tricks?” – providing useful examples and illustrations of the techniques in action.

Five tools for managing tensions

1. Listening Skills

Sometimes conflict arises simply because people do not feel heard, so just making the time for them to speak, and actively listening to them, can take the sting out of a situation and help you to more easily negotiate a resolution

Active listening involves just listening and nothing else. In everyday speech there is an overlap between listening, thinking and speaking – we are often trying to do all three at once! However, this means we are not really paying attention to the person we are listening to and we may miss some of the meaning of what they are saying. Also, we are often thinking about what our response will be rather than what the other person is actually saying.

- Active listening is more easily described than done, so Chapter 2 includes an active listening exercise if you would like a bit of practice

Accentuate the positive. Eliminate the negative. Latch on to the affirmative. Don’t mess with Mr. Inbetween.

2. Assertiveness

In a co-operative, where management is democratic and where good teamwork is essential, it is vital for people to understand how to behave assertively – i.e. knowing their own mind and standing up for themselves and their own opinions, without being pushed around by others (and without pushing others around).

In contrast, people often behave in ways which are either:

- Aggressive – trying to get their own way by bullying or other power strategies

- Passive – accepting other people’s opinions or decisions without thinking for themselves

- Manipulative – using underhand or devious strategies to get their own way

Assertive behaviour is much less likely to lead to conflict. Below is a technique for giving criticism assertively which will help to bring about the changes you want without causing hurt or offence to the recipient.

- Do not use this as an opportunity for a put-down. You need to be clear yourself about the behaviour that you would like your colleague to change. It’s important that you address the behaviour and not attack the person.

- Remember you both have rights. You have the right to expect colleagues to deliver to a standard you have all agreed and your colleague has the right to be treated with respect.

- Find a time and a place where you can speak privately.

- Be specific about the change you want and talk about behaviour you can see. Talk about facts not your opinions.

- Do this as soon as possible after realising the impact your colleague’s behaviour is having. Don’t let it build up until you are angry and resentful.

- Ask your colleague how they see the situation and try to get them to work with you to bring about change.

- Chapter 2 has further guidance on giving and receiving criticism assertively

3. Dealing with tension in the workplace

Use this well tried-and-tested formula for dealing with tension between individuals in the workplace. These guidelines can be used by the protagonists or by other members of the team. The aim is to be constructive and to seek changes that will make everyone happy, rather than attempting to ‘win’.

Again, it’s important to be specific, talking about actions not opinions, facts not accusations, examples not generalisations. Talk about how you feel (i.e. angry or disappointed) and be clear about what you want to change. Be positive – i.e. ask the person to start or increase doing something (not to stop doing something).

Explain why, as it helps if they understand your reasons:

- “When you do (or did)………………………..” (concrete example)

- “I feel……………………………………………….” (acknowledge your feelings)

- “And I want you to……………………………..” (specific concrete request)

- “Because………………………………………….” (your reasons)

- “Do you agree?…………………………………” (try to reach agreement)

Smooth seas do not make skilful sailors.

4. Reframing

Mediators use a technique known as reframing which can help people communicate in stressful situations. Basically, it involves restating what the other person has said, in a way which illuminates their intent while not losing the essence of the message. This can help both listener and speaker clarify the issues.

- We describe the technique in more detail in Chapter 2 Communication

5. Mediation

If the techniques listed above have not helped, we recommend using mediation to resolve the conflict. A mediator can help you reach an agreement to change behaviour. Any agreement comes from those in dispute, not from the mediator. The mediator does not judge or tell them what to do (beyond making suggestions). The mediator is in charge of the process of seeking to resolve the problem but is not responsible for the outcome. Rhizome is a worker co-operative that offers mediation as well as running communication and conflict training sessions. You could also try Navigate, Seeds for Change or Resist and Renew

Summary

Conflict is part of life. It is evidence that there is a wealth of experience, knowledge and ideas in the group. So some conflict is inevitable and we need to know how to deal with it in a constructive way when it arises

- We identified a range of possible causes of conflict in a co-operative

- We reviewed five typical approaches to resolving conflicts – and the advantages and drawbacks of each

- We presented the techniques of Principled Negotiation, based on the book Getting to Yes by Fisher & Ury

- Lastly we listed five tools for managing tensions before they erupt into conflict